Tricked by Design: Deceptive Patterns in Indian Fintech Apps

We conducted an audit of popular fintech apps and assessed for deceptive design used by them. Here's what we found.

The Indian fintech industry has seen a rapid rise due to widespread digital adoption (with over 700 million smartphone users1), mature data ecosystems (with initiatives such as the account aggregator), and cross-selling of multiple financial products (resulting from a large, consolidated user base through unified payments interface, UPI). While this growth is driving a potential USD 1 trillion market2, there are significant concerns over the potential risks posed to users in terms of privacy and financial harm.

For instance, the fintech industry tends to use deceptive patterns3 like hidden costs, expensive surrender clauses, misleading games, and bundled products; with the ultimate motive of higher and faster business growth. For a country with stark inequalities like India, the impact of such deceptive designs can have stronger negative effects on constrained users.

This study was conducted to identify the deceptive patterns that a user can face while using popular Indian fintech apps and the intended harm that they can potentially cause. Literature on deceptive patterns in India is mostly restricted to e-commerce4 and occasionally to fintech users5. However, with a field as dynamic as fintech, up-to-date research on deceptive patterns is always a work in progress. This study aims to work towards filling that gap.

Methodology

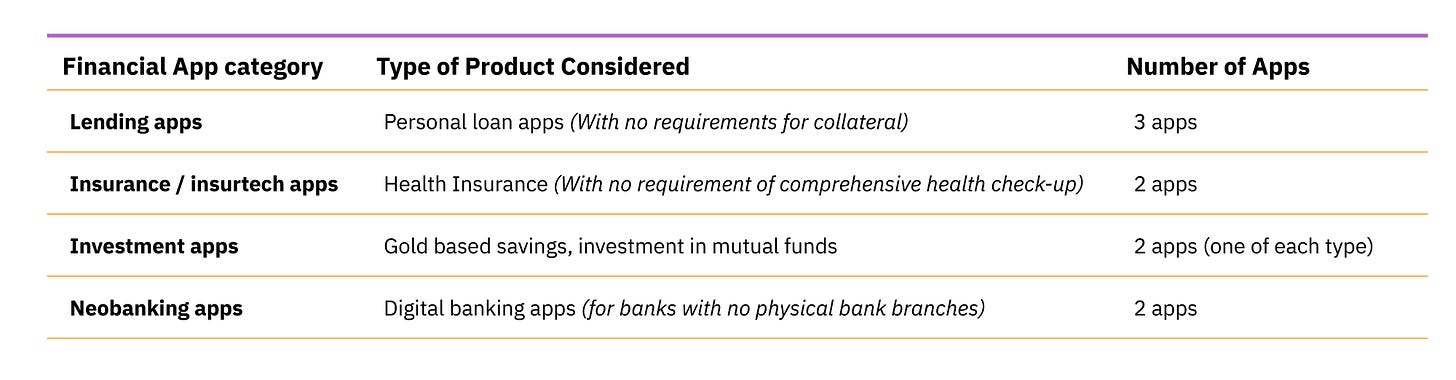

We selected retail financial products delivered through fintech applications on a smartphone. Our sample consisted of nine popular apps from four categories of financial services - lending, insurance, investments, and neo-banking. For each app, we assessed their relevance and popularity metrics such as the number of downloads and ratings on Android/iOS app stores. We restrict the analysis to apps that have been operational for a period of at least 12 months at the time of selection. Although our list is not exhaustive, these popular apps play a role in setting the industry standard for designing user experiences.

We downloaded each of these apps and examined the user flow with the intention to detect and identify deceptive patterns at various stages of the customer journey.

After this stage, we categorized our observations from each application, by the types of deceptive patterns as reviewed in the literature. In the app review process, we found that the existing taxonomy of deceptive patterns was limited in the context of India, and therefore, a section of the research had to be devoted to creating a usable taxonomy that fit our observations. Finally, we mapped the deceptive patterns observed against the various types of harm they can cause to the user.

Deceptive patterns found in Indian Fintech Apps

Deceptive patterns in commercial practices have been well established in contemporary literature by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)6. We follow the definition provided by the Stigler committee report on Digital Platforms which articulates that deceptive designs are “user interfaces that make it difficult for users to express their actual preferences or that manipulate users into taking actions that do not comport with their preferences or expectations.”

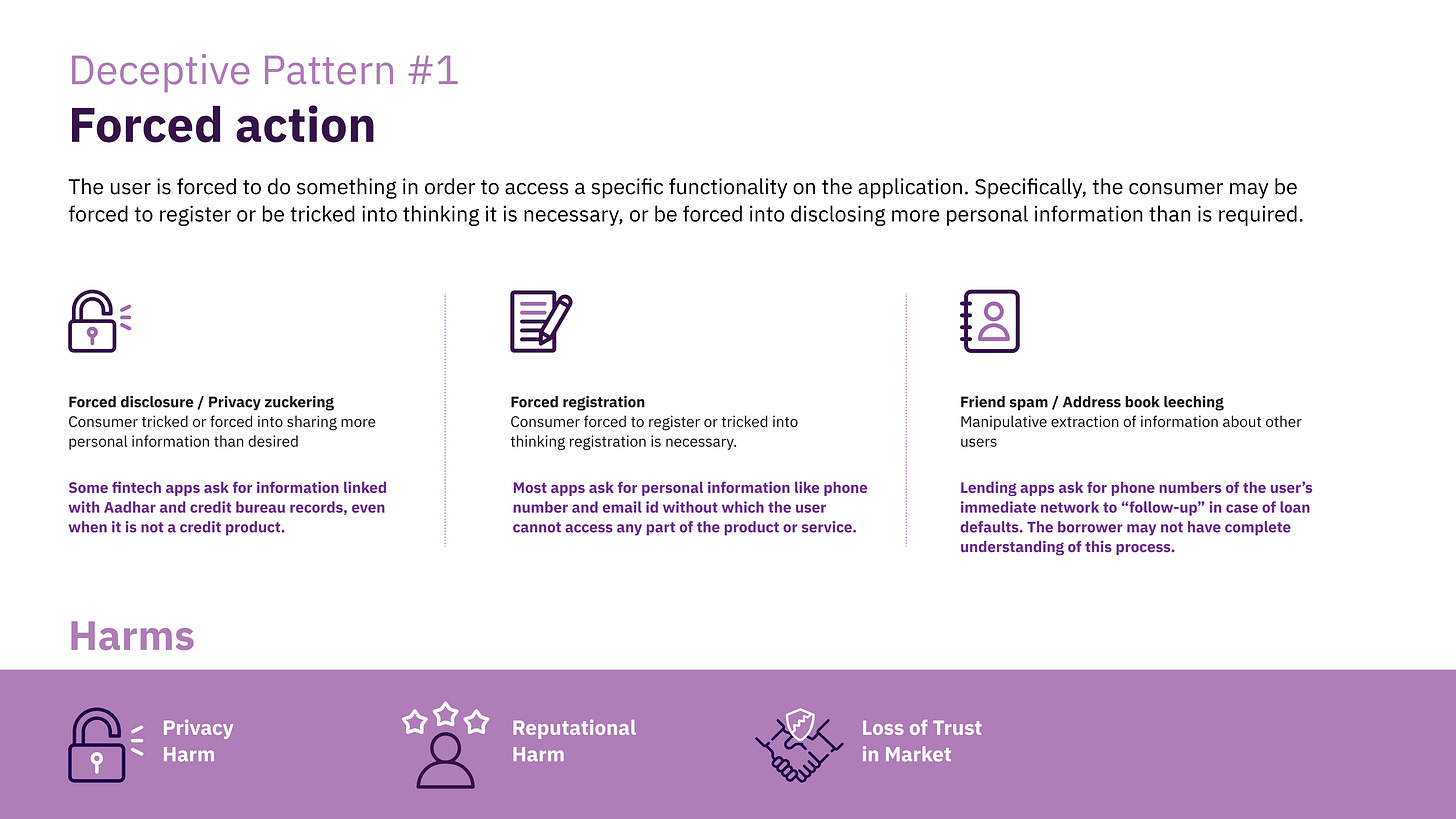

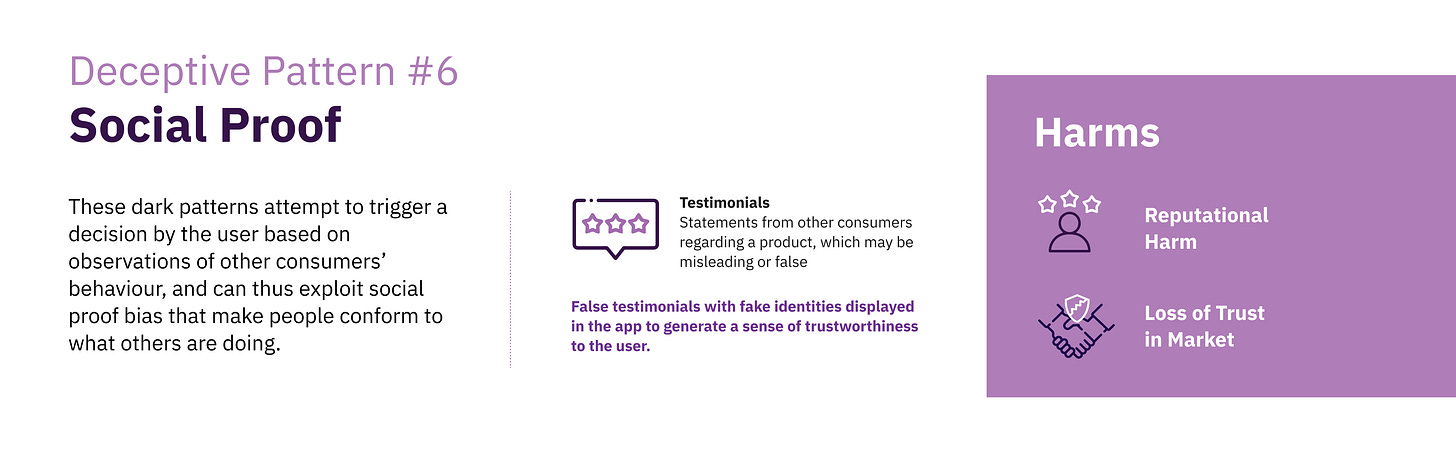

We broadly use the taxonomy by OECD to categorize our findings of deceptive design across the selected fintech apps. Our assessment reveals the presence of seven categories of deceptive patterns including forced action, interface interference, nagging, obstruction, sneaking, social proof and urgency. The infographics below provide a description of each category and the harms associated with it.

User harm caused by deceptive patterns in fintech apps

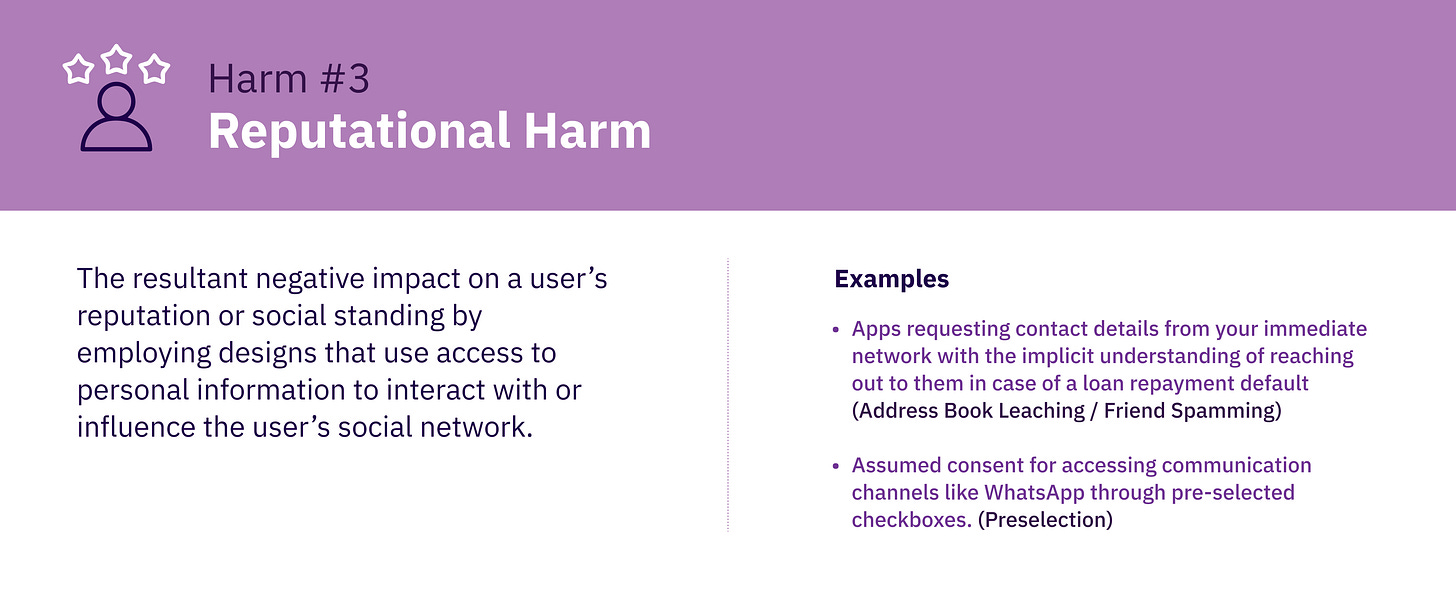

Deceptive patterns in fintech apps are deployed to compete for market share, meet their aggressive sales targets, and create a loyal base of customers by making it difficult for them to leave the app7. However, for the end consumer, deceptive patterns often lead to harm such as invasion of privacy, intended financial loss, psychological burden, loss of societal reputation, and erosion of trust in the market. While certain deceptive patterns pose a higher degree of threat than others, for the purpose of this study, we refrain from creating a scale for the extent of harm a deceptive pattern might cause. The infographic below discusses the harms caused by deceptive patterns observed in Indian fintech.

Sometimes, a specific deceptive pattern can lead to more than one kind of harm. This will be discussed in the next section.

Evidence of deceptive pattern in Selected fintech Apps

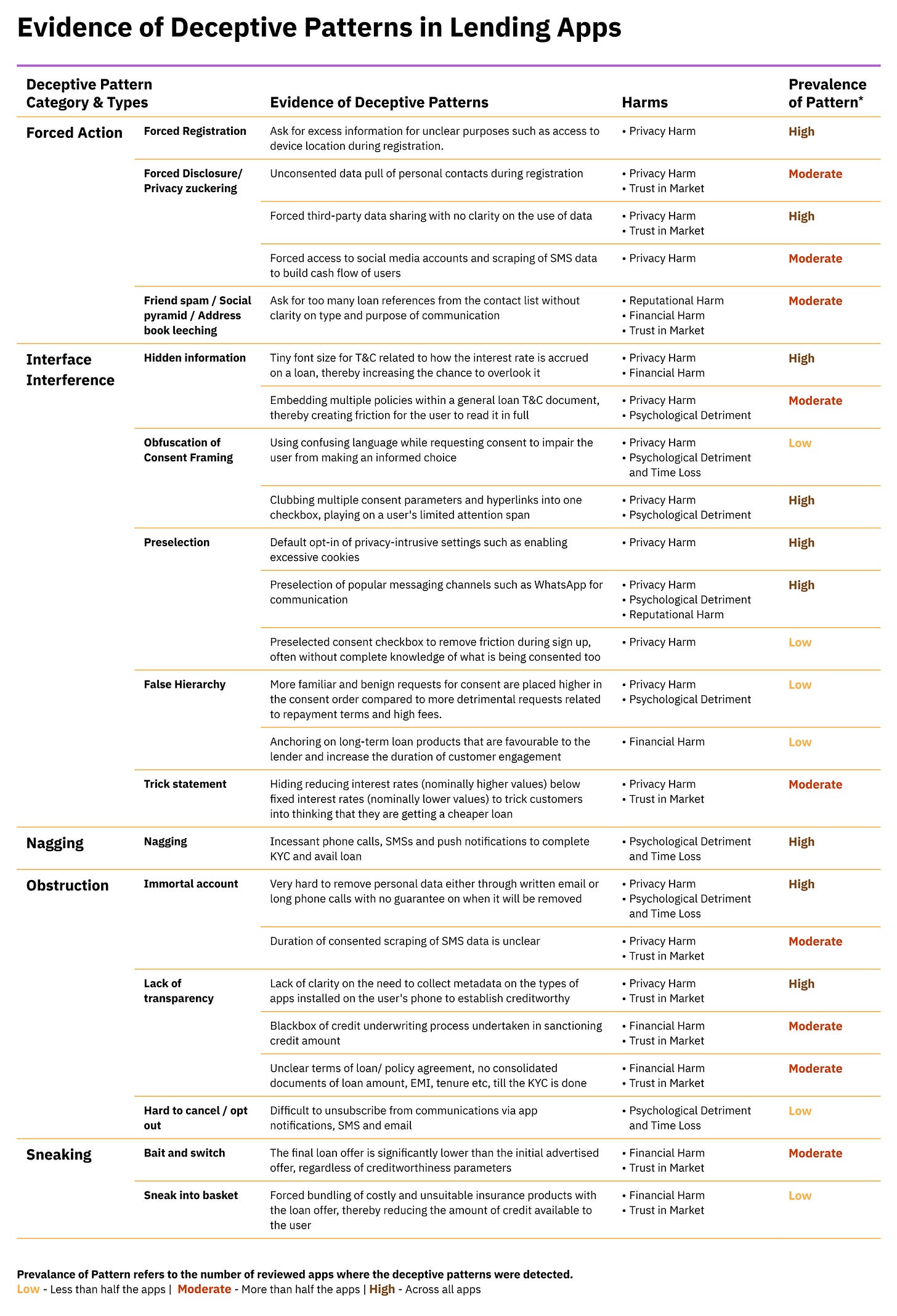

Lending Apps

Fintech lending apps use alternate data sources and algorithms to offer personalized and low-ticket loans to borrowers who may not have detailed credit histories. A typical user flow involves sign-up. The app access data from multiple sources and require users to complete KYC before making a loan offer. We identify several deceptive patterns that have been observed at various stages of the user journey.

Through forced action, apps request access to excess information such as scraping of SMS data and social media accounts without explicitly mentioning its purpose. Address book leaching and asking for too many loan references was common practice. We observed several complaints on social media platforms about user contacts being subjected to nagging with marketing calls and loan offers. Access to data is also procured through interface interference by hiding important information. Clubbing multiple consent requirements and hyperlinks into one checkbox and pre-selection of options that may be a more privacy-intrusive play on a user’s limited attention span and time.

The loan offer itself is laden with obstruction and interface interference, aimed at deceiving the customer through a lack of transparency. This includes unclear terms of loan/ policy agreement, no consolidated documents of the loan amount, EMI, tenure, etc, till the KYC is done. Bait and switch strategy was common in lending where the final loan offered was significantly lower than the initial advertised offer. Often sneaking in unrelated and unsuitable financial products such as health insurance was found as a way of cross-selling.

These deceptive patterns in addition to immediate financial costs, can impact a user’s future creditworthiness by reducing their credit scores. Lack of transparency also leads to a loss of trust in the market.

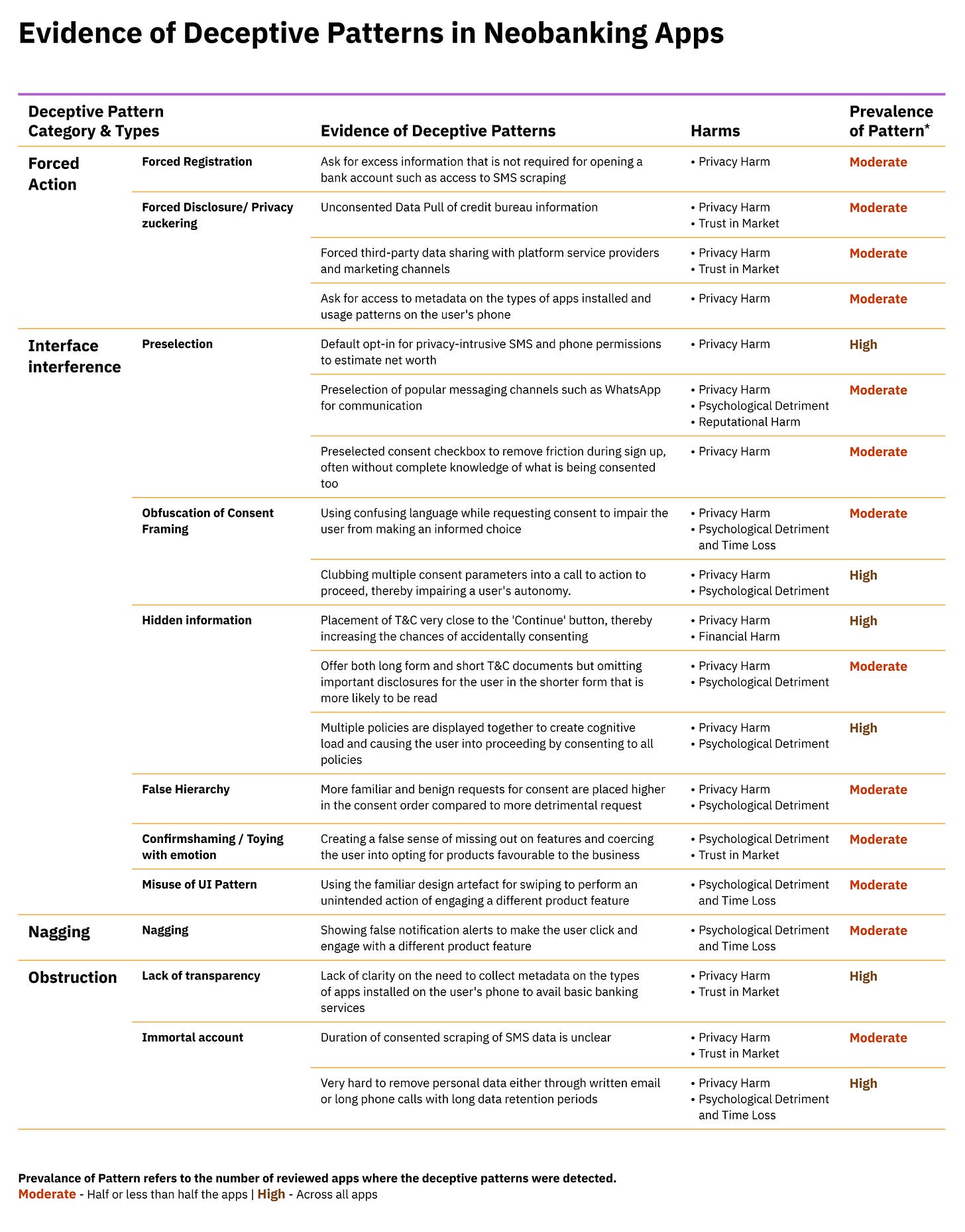

Neobanking Apps

Neobanking apps typically leverage the user’s current behaviour to design banking solutions that are user-friendly and engaging. They offer convenience but also leverage user behavioural bias to offer products and services that may not be in the user's best interest.

A typical app flow involves a mandatory sign-up, followed by consenting to access and sharing of multiple data parameters (including the regulated banking entity offering the account and other third parties), and a minimum KYC process mandated to open a bank account. Once the account is set up, the app tries to cross-sell multiple other offerings beyond basic banking.

Forced action is used to gain access to excess information, that is not needed to open a bank account including metadata and apps on the users’ phone. Forced data sharing with all third-party service providers (credit bureau information) means that users can’t choose what financial products they want to engage with. Several interface interferences were employed to coerce data sharing synch as using false hierarchies to display more benign requests for consent higher in the order compared to more detrimental requests. Hiding information by offering both long-form and short T&C documents but omitting important disclosures in the shorter form that is more likely to be read is commonly seen. After account opening, the apps constantly push multiple financial products to users packaged as ‘upgrades and Confirm shaming language is used to create a false sense of missing out on features and coercing the user into opting for products favourable to the business. Misuse of UI patterns is employed to utilize familiar design artefacts like swiping to push new products. Designed to be immortal accounts, these apps use obstruction to make it very hard to remove personal data if the user decides to discontinue using the service or have long periods of data retention. Our observations reveal severe privacy harms for the user from consenting to significant amounts of personal data and forced sharing of this data with third parties

.

Insurtech apps (Health Insurance)

Traditionally, the process of selling an insurance policy has been offline at a bank or through an insurance agent. However, Insurtech enables the wider distribution of products as well as fulfils business targets. The problem arises when some of the design aspects found within Insurtech Apps do not have the end user’s best interest and can pose significant harm.

Buying a health insurance product usually requires a prior health checkup at a hospital, based on which the insurance company calculates the premium amount. In our study, we found InsureTech apps practised forced action to gather information on the insuree’s health conditions that however had no bearing on the insurance policy premiums, even after setting it at the worst health parameters. Similar to lending and neo-banking apps, multiple interface interference design patterns were used to obfuscate a user’s consent of various pertinent terms and conditions.

In the app flow, when the user is likely to make a purchase decision for specific products, insurtech apps often use false hierarchy wherein higher priced options, that may not be suitable to the user, are anchored by a “popular tag” and given visual prominence. These apps also use a deceptive pattern called Urgency, wherein a countdown timer creates an arbitrarily limited upgrade offer to rush the user into purchasing products that are favourable for the business but not necessarily for the end user.

Overall, InsureTech apps use deceptive patterns like false hierarchy, urgency, hiding information, and obfuscation of consent to pressure users into buying a policy, which can lead to privacy harm, erosion of trust in the digital market, and psychological detriment.

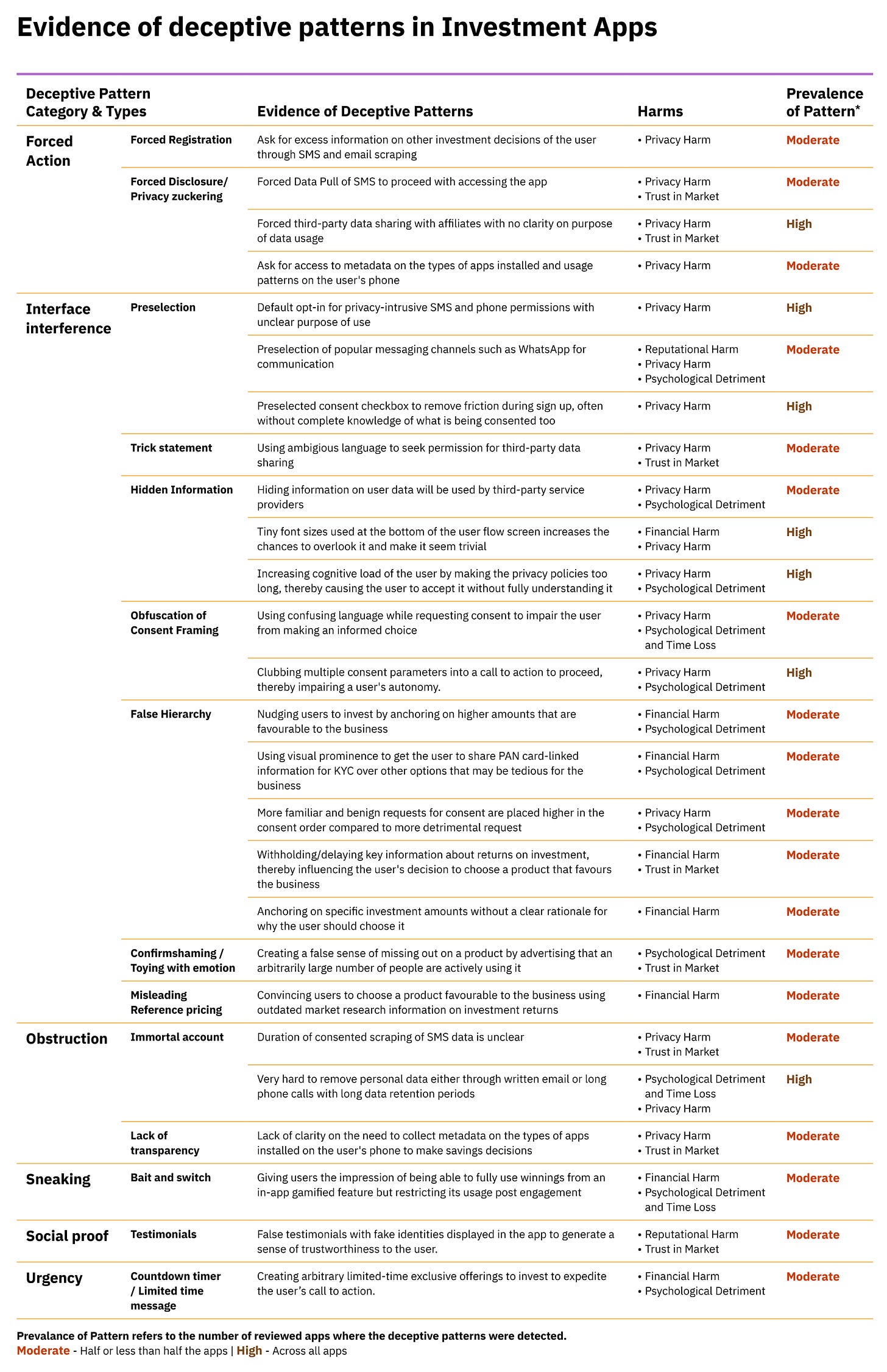

Investment Apps

Investment apps or saving apps can help users to navigate options and allocate their money towards various funds, schemes, and products. Despite being a heavily regulated industry in India, some investment apps in this study have been using problematic deceptive patterns to acquire, retain and engage with users.

One of the most alarming deceptive patterns used by investment apps is when they forbid users to continue if they disagree to allow transaction SMS scrapping on their phone. Through forced action, investment apps coerce users to consent to privacy zuckering options such as consenting to share all transaction data through SMS and email scrapping as well as sharing that information with third-party affiliates with the unclear purpose of usage.

Investment apps use deceptive patterns such as forcing users to agree to SMS scrapping, illegible font size for terms and conditions, false hierarchies, misleading reference prices, and social proof deception to acquire, retain and engage customers. These deceptive patterns lead to privacy and financial harm and should be regulated.

Lastly, in case a user wants to stop using these apps, it is very hard to remove personal data from the app’s database. This is done by creating an obstruction where the user is either asked to write an email to the company or go through a long phone call. A user with time and cognitive constraints is unlikely to do either of these two, thus consenting to an immortal account by default.

Conclusion

Deceptive design can cause varying degrees of harm to users. However, incorporating ethical design in the user experience can often be at odds with short-term business motivations, particularly pressured by the need to match up to the astronomical valuations that several fintech startups have received. The fintech industry’s valuation is expected to grow 3.5 times by 20268. Evidence from literature9 also suggests short-term financial gains from employing deceptive designs (such as users paying higher than required prices), which explains their prevalence. In some cases, the design aimed at improving the user’s experience (such as pre-selection) may unintentionally become deceptive for the user. Regardless, repeated exposure to such deceptive designs can have longer-term implications by lowering trust in the market itself. Designing ethically need not be a significant compromise on business outcomes or user experience, we explore this in the second part of our blog.

This study has been supported by Pranava Institute. The blog was first published on their website.

All artworks are designed by Himanshi Parmar and Rajashree Gopalakrishnan.

If you enjoyed reading this blog and would like to receive more such articles from D91 Labs, please subscribe to our blogs here.

To read more about our work, visit our website

You can follow us on Twitter | LinkedIn | Instagram | WhatsApp

Press Trust of India. (2022, February 22). India to have 1 billion smartphone users by 2026: Deloitte report. www.business-standard.com. https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/india-to-have-1-billion-smartphone-users-by-2026 -deloitte-report-122022200996_1.html

The Hindu. (2022, September 20). Indian FinTech market to reach $1 trillion by 2030, says CEA. https://www.thehindu.com/business/indian-fintech-market-to-reach-1-trillion-by-2030-says-cea/article65915 274.ece

Stigler Committee on Digital Platforms: Final Report. (2019, September). The University of Chicago Booth School of Business. https://www.chicagobooth.edu/research/stigler/news-and-media/committee-on-digital-platforms-final-report

M. Bhoot, A., A. Shinde, M., & P. Mishra, W. (2020, November). Towards the identification of dark patterns: An analysis based on end-user reactions. In IndiaHCI'20: Proceedings of the 11th Indian Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 24-33). https://doi.org/10.1145/3429290.3429293

Chugh, B., & Jain, P. (2021). Unpacking Dark Patterns: Understanding Dark Patterns and Their Implications for Consumer Protection in the Digital Economy. RGNUL Student Research Review Journal, 7, 23. http://rsrr.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/UNPACKING-DARK-PATTERNS-UNDERSTANDING-DARK. pdf

OECD (2022), "Dark commercial patterns", OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 336, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/44f5e846-en.

Newcomb, S. (2022, September). Buyer, Beware! Your Brain on Fintech. Morningstar UK. https://www.morningstar.co.uk/uk/news/226772/buyer-beware!-your-brain-on-fintech.aspx

Mint. (2022, October 25). Fintech valuations to rise 3.5 times by FY26: Bain study. https://www.livemint.com/companies/news/fintech-valuations-to-rise-3-5-times-by-fy26-bain-study-116667 20221958.html

Blake, T., S. Moshary, K. Sweeney, and S. Tadelis (2021). Price salience and product choice. Marketing Science 40 (4), 619–636. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2020.1261