Can ‘e-RUPI’ enable digital payments for the unbanked?

In our second blog of the Digital Payment for the Next Half Billion series, we explain the e-RUPI voucher-based payment, its usefulness for 'Bharat' and potential design flaws that could derail it.

Manjunath (45), a small land-owning farmer, stands in a long queue outside of a Cash Out Point (COP) near his village in rural Karnataka. He had enrolled himself in a Central Government Scheme last year that would give him a cash benefit of Rs. 6,000 every year to buy inputs for his farming activities. With erratic weather patterns becoming a common feature of agriculture in India, he was not able to earn as much as he had anticipated with his previous harvest. He looks forward to the Government’s transfer as a means of buying the inputs such as seeds and fertilizers for the upcoming sowing season. Manjunath is not alone. A survey shows that around 21% of a farmer's income per hectare in India is facilitated by government subsidy expenditure1.

Manjunath waits patiently for his turn to receive the subsidy amount. Unfortunately, the bank agent has run out of cash owing to the rush to redeem subsidy money at the beginning of each month. Disappointed, he returns home with nothing to show for his efforts. He returns to the Cash Out Point early the next day and is pleased to be among the first customers in line. He is confident he will get the subsidy money today. However, while completing his transaction, there is some issue with the biometric authentication device! Nearly 1 in 5 AePS transactions result in failures due to technical issues2. The agent is unable to process the payment. Manjunath pleads with the agent to help him out with getting the money as his house is several kilometres away. The unscrupulous agent calls him to the side and asks him to meet him in the afternoon where, for a small extra ‘fee’ (read as a bribe), he would ensure that the payment is processed the same day. With the sowing season already in full swing, Manjunath, in desperation, agrees to give the agent a cut in return for processing his transaction.

These experiences and challenges are all too common when it comes to providing banking services for the last mile. What if Manjunath could be spared from this harrowing experience? What if he did not have to go to a Cash out Point altogether to avail the benefits of the subsidy? What if he could receive these benefits even if he did not have an active bank account and not having to deal with intermediaries like the agent? What if, in the process, he could also start transitioning into making payments digitally using the massively popular UPI platform as well?

Sounds like wishful thinking?

Enter ‘e-RUPI’ - Not to be confused with RBI’s digital rupee (CBDC3) that has been making waves these past few months…

The ‘e-RUPI’ is an innovative digital payment solution launched by the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) in association with the Department of Financial Services (DFS), the National Health Authority (NHA), the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), and partner banks. It is a purpose-specific and person-specific voucher-based mobile payment mechanism that can be redeemed through an SMS or QR code seamlessly without a card, digital payments app or internet banking access, at merchants accepting e-RUPI on the UPI railroads.

Still confused? Let’s look at an example that may be a bit more relatable… e-Gift Cards!

We’ve all probably had a situation where we don’t know what to gift someone for an upcoming birthday or a wedding. E-gift cards have been a lifesaver for me personally. It avoids pointless debates about what kind of gifts people want and whether they already have them! The person receiving it has all the convenience of choosing whatever they’d like to buy from Amazon, Flipkart, MakeMyTrip or whatever e-commerce platform the gift card is issued from.

Now imagine extending this concept of providing vouchers or ‘gift cards’ to the entire social security payments framework and allowing, even incentivising beneficiaries to spend this money for specific purposes from any business that accepts payments through the UPI platform.

Yet another instrument for digital payment! How is it any different… and how does it help the cause of financial inclusion?

To summarize this in two words… ‘Fewer Prerequisites’... for accessing digital payments.

No requirement for a bank account

While India has more than doubled financial account ownership among its population in the past 10 years, it is still home to about 230 million individuals who remain unbanked! What’s more, unlike most developed economies, bank account ownership, especially in rural areas remains a household-level product, i.e. multiple members of the household access the same bank account. This makes it difficult to access specific individuals within the households, especially due to prevalent social constraints or low financial literacy, such as women or the elderly respectively. e-RUPI does not require access to a bank account to enable the usage of the issued voucher. By eliminating the need to share personal or financial account details during redemption, the beneficiary’s privacy can also be maintained

No requirement for a smartphone

While smartphone technology is becoming cheaper, its ownership has increased exponentially in India. Despite this, over 450 million people continue to use ‘keypad’ feature phones. Many of the hugely popular digital payment mechanisms such as the UPI remain out of reach for this group despite innovations such as UPI123 or UPI Lite (we cover this in detail in our earlier post). These channels continue to be heavily skewed in favour of smartphone users. The e-RUPI voucher can be accessed using an alphanumeric string code that can be shared via an SMS to the recipient, making it easy to redeem even using a basic feature phone.

No need for a UPI App or prior knowledge of making digital payments

With UPI transactions reaching INR 11.16 lakh Cr. in September 2022 and being conducted across nearly 19000 pin codes all over India, those who don’t currently use the UPI platform are largely the digitally non-native cohort with very low digital and financial literacy. This limits the complexity of digital interactions that can be achieved by this cohort. Even among smartphone users within the cohort, the use is largely limited to messaging, entertainment and social media platforms. e-RUPI solves this lack of familiarity by not requiring the use of any UPI application or prior knowledge of making digital payments to redeem the value of the issued voucher. e-RUPI has the potential to introduce familiarity with transacting digitally for the digital non-native cohort as the redemption mechanism is similar to conducting a normal UPI merchant transaction.

Alright… so is this useful only for making government welfare payments?

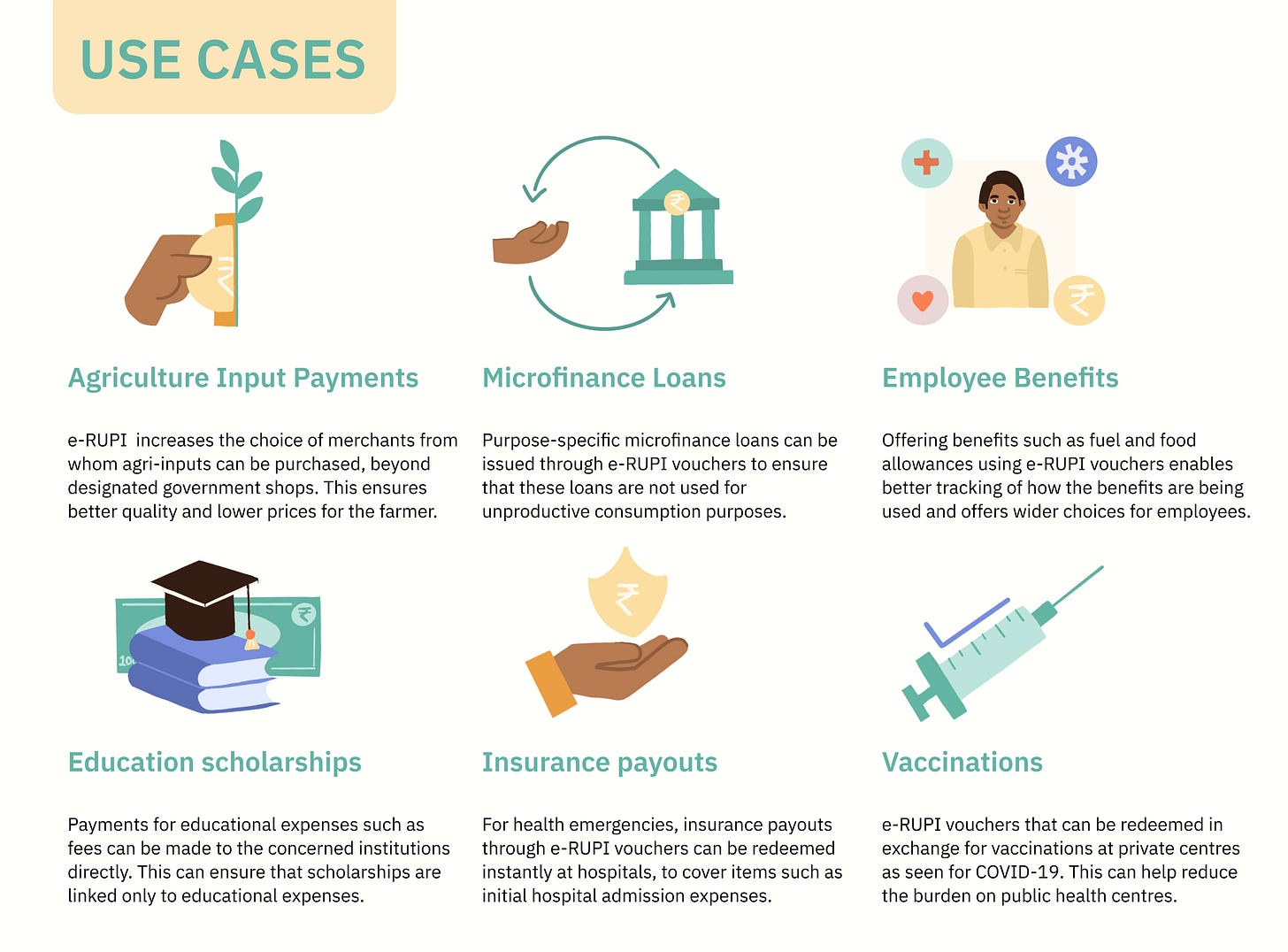

While social security and welfare payments from the Government come across as the most obvious use case for the e-RUPI, the possibilities are numerous. An e-RUPI voucher can be sponsored by private entities such as corporates and individual sponsors. We highlight some potential use cases for the e-RUPI:

And so much more!

Why does the Government want to promote this voucher-based payment?

The government's push for Direct Benefit Transfers (DBT) over the past decade has helped streamline welfare systems and aimed to ensure that the correct beneficiaries received assistance without leakages.

However, studies4 have highlighted various barriers to ‘accessing’ welfare benefits across four stages of the delivery chain in terms of identification, targeting, payment processing, and cash withdrawal. Notably, payment failures during back-end processing emerge as a significant concern – where enrolled beneficiaries do not receive the DBT in their bank accounts for various reasons. In a recent survey5, nearly 3 out of 4 respondents reported experiencing issues while processing G2P payments. Over 18% of these cases were on account of ‘Bank Account and Aadhaar-related issues’, indicating that beneficiary payments failed due to errors in their Aadhaar IDs, KYC process, Aadhaar-bank account seeding process or money going to a different account than those being actively used.

Findings from another study6 suggest that the cost of accessing direct transfer payments also varies across beneficiaries. For those using ATMs, it costs less (in time and money) to access cash and buy grains from the market than to collect Public Distribution System (PDS) rations directly. However, for beneficiaries who had to use a bank branch or a cash-out point, like Manjunath, it cost more to access cash and purchase commodities from the markets than the original PDS arrangement.

While direct benefit transfers have made using welfare payments more convenient and flexible, this has introduced a problem of a different kind, a lack of transparency over how the payments were being utilized by the intended beneficiaries. With the e-RUPI, the sponsor can restrict where the voucher can be redeemed.

For example, if a voucher has been issued for the purchase of tuberculosis (TB) medicines, the voucher may only be redeemed at drug stores or pharmacies. This is enabled by using the Merchant Category Code (MCC)7 which is issued to every merchant who is on UPI or other digital payment platforms such as credit cards to describe the types of goods or services they provide. This enables more transparency and efficiency by…

Enabling a near real-time tracking of a targeted Government Scheme/ Programme

Lowering the cost of distribution to beneficiaries (particularly those who are unbanked or underbanked).

So… what’s in it for the household receiving these benefits? How is this better than cash? Also, are there any benefits for women in these households?

The e-RUPI mechanism has the potential to enable better targeting of members within a household as well. Several research studies8 have highlighted that women are better at financial decision-making, particularly in the context of lower-income households. They are more inclined to allocate household financial resources to productive use such as education and healthcare. In practice though, large-ticket financial decisions in Indian households continue to be made primarily by male members9. While many social protection schemes have been targeted primarily at women by linking benefits to their bank accounts, the DBT mechanism still does not offer agency to the woman regarding how the transfer is eventually utilized. Often, the transfer is added to a common pool of money that the household has and the male member decides how it is spent. e-RUPI can address this by limiting the purposes for which the money can be utilized by members of the household.

What’s more... it has the potential to reduce privacy concerns, particularly for women, as no personal or financial information such as the bank account number, name or phone number needs to be shared with the merchant to redeem the voucher.

e-RUPI is likely to find favour with merchants as well as they can be redeemed quickly in a few stages with smaller transaction declines because of the pre-blocked value linked to the voucher. Further by running on the UPI railroads, the voucher should potentially increase the household’s options in terms of where to avail of a particular product or service, as opposed to in-kind benefits such as purchasing food grains from specified ration shops.

Sounds lovely… but are there any potential red flags?

e-RUPI, like any other medium, is not without its limitations. It must be seen as an incremental step in supplementing and making digital payments a reality for the unbanked and underbanked segments. The inherent challenges with existing social welfare schemes such as identification and the inclusion or exclusion of the correct beneficiaries though remain largely unaddressed.

Another challenge concerns merchant acceptance of e-RUPI. The flip side of making digital payments easy for the customer is that the prerequisites for acceptance among merchants will increase. Merchants will at least require access to a smartphone to scan and enable redemption of the voucher. While UPI acceptance is quite high among even micro-merchants across the country, this does not mean they can engage with and use the UPI platform themselves. These frictions for merchants may negatively impact the acceptance infrastructure for e-RUPI and reduce the potential benefit it could bring in.

Most importantly though, treating mobile phone numbers as the primary mode of verification of a beneficiary is highly problematic. In recent years, more and more platforms and services have come to rely on mobile numbers to confirm—or "authenticate"—users. In theory, this makes the process very convenient. However, in practice, it means that a single, often publicly available, piece of information gets used both as your identity and a means to verify that identity. This is particularly true in rural households with a common phone and limited control over who may use it. This can lead to significant increases in fraudulent transactions, particularly as several cohorts that stand to benefit from the e-RUPI are technologically less savvy.

With the NPCI highlighting that over 74 Government Schemes amounting to over Rs. 36000 Cr. have the potential of being delivered through the e-RUPI platform, it is crucial that the beneficiary authentication process be designed to be more secure while retaining the elements of simplicity that make it conducive for use within the Bharat segment.

Part of our series on Digital Payments for the Next Half Billion

With transactions worth INR 11.16 lakh crores clocked in September 2022, the impact of UPI in furthering the digitization of payments is unprecedented. The next wave of growth is likely to come from Tier 3-6 locations, as evidenced in the past two years wherein these cities have contributed to nearly 60-70 per cent of new mobile payment customers. Recent initiatives from the NPCI have highlighted the need to make digital payments accessible for all. With digital payments deepening financial inclusion, we explore the opportunities and challenges that these new initiatives offer to the next half billion through this series.

All artworks are designed by Himanshi Parmar.

If you enjoyed reading this blog and would like to receive more such articles from D91 Labs, please subscribe to our blogs here.

To read more about our work, visit our website

You can follow us on Twitter | LinkedIn | Instagram | WhatsApp

https://fincomindia.nic.in/writereaddata/html_en_files/fincom15/StudyReports/Agricultural%20subsidies.pdf

https://www.dvara.com/research/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Transaction-failure-rates-in-the-Aadhaar-enabled-Payment-System-Urgent-issues-for-consideration-and-proposed-solutions.pdf

Central Bank Digital Currency in India also known as the ‘digital rupee’.

https://www.dvara.com/research/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/State-of-Exclusion-Delivery-of-Government-to-Citizen-Cash-Transfers-in-India.pdf

https://www.dvara.com/research/blog/2022/07/04/payment-failures-in-direct-benefit-transfers/

https://www.ideasforindia.in/topics/governance/need-for-a-choice-based-approach-in-pds.html

A Merchant Category Code is a four-digit number that identifies the type of products or services the merchant provides. They were mandated to facilitate tax reporting. Currently, the MCC guidelines are maintained by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).

http://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/127840/filename/128051.pdf

Kurian, V., Sreedharan, S., & Valenti, F. (2022). Calling the Shots: Determinants of Financial Decision-making and Behavior in Domestic Migrant Households in India. Journal of Emerging Market Finance, 21(3), 317–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/09726527221082005