Banking for Rural Bharat

Serving rural India needs better access to financial products. Among other things, they need phygital services, customer education, and suitable products.

“Banking is necessary, but banks are not” – Bill Gates, 1994.

This was a powerful statement for the 1990’s. Up until then, an individual’s bank was an integral (albeit, sometimes formidable) institution, a partner at every stage of life. As the world spun towards the new millennium, the wisdom of Bill Gates’ statement was proved across multiple economies, with market disruptions in financial services, led by technological advancements and changing consumer trends.

In India too, there has been a dramatic shift in the way banking is offered and delivered. In fact, the new age of banking led to a range of possibilities that could now cater to the traditionally underserved segments and rural regions of the country – collectively known as Bharat. Comprising roughly 70% of the country’s population, Bharat is rapidly contributing to shaping the economy for the future.

Historically, Banks have faced massive operational, economic, and cost challenges in seamlessly delivering financial services to the hinterlands of India. Thus, for the past few decades, providing access to financial services for all has been led primarily by the Government, in tandem with banks, regulatory bodies, and fin-techs. Seen as a driver of economic growth, poverty alleviation, and prosperity, access to banking and financial inclusion has become a focal point in Government planning.

Where does Banking for Bharat stand today?

While multiple initiatives have been undertaken in the last couple of decades, we ponder on a few that have focused on setting up the prerequisite infrastructure to pave the way towards financial independence.

From 2004 to 2015, the Aadhaar based identification layer was implemented, enabling access to financial services for most. Backed by an increase in internet and mobile services across rural regions, Aadhaar is the base layer of the India tech infrastructure – providing identity and authentication services to all.

For the resident of, say, a tier-5 village in Bharat, the Aadhaar card facilitates access to multiple services – from basic financial services, insurance, to health records and telecom services.

Next came the provisioning of a transaction account to all adult Indians, a fundamental step in accessing financial services. The Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojna (PMJDY) scheme, launched in 2014, played a vital role here, with the creation of Basic Savings Bank Deposit Accounts (BSBDA), which are no-frills, zero balance accounts that can be linked to RuPay debit cards. For Bharat, the presence of a bank account introduces services such as deposits, withdrawals, and payments. In turn, this serves as a gateway to a broader suite of financial offerings such as credit, insurance, pension amongst others.

The central bank, too, passed several directives and regulatory reforms to strengthen ties between banks and Bharat leading to the setting up of rural branches, installing new ATMs/White-labeled ATMs (WLAs), and leveraging the Business Correspondent (BC) model.

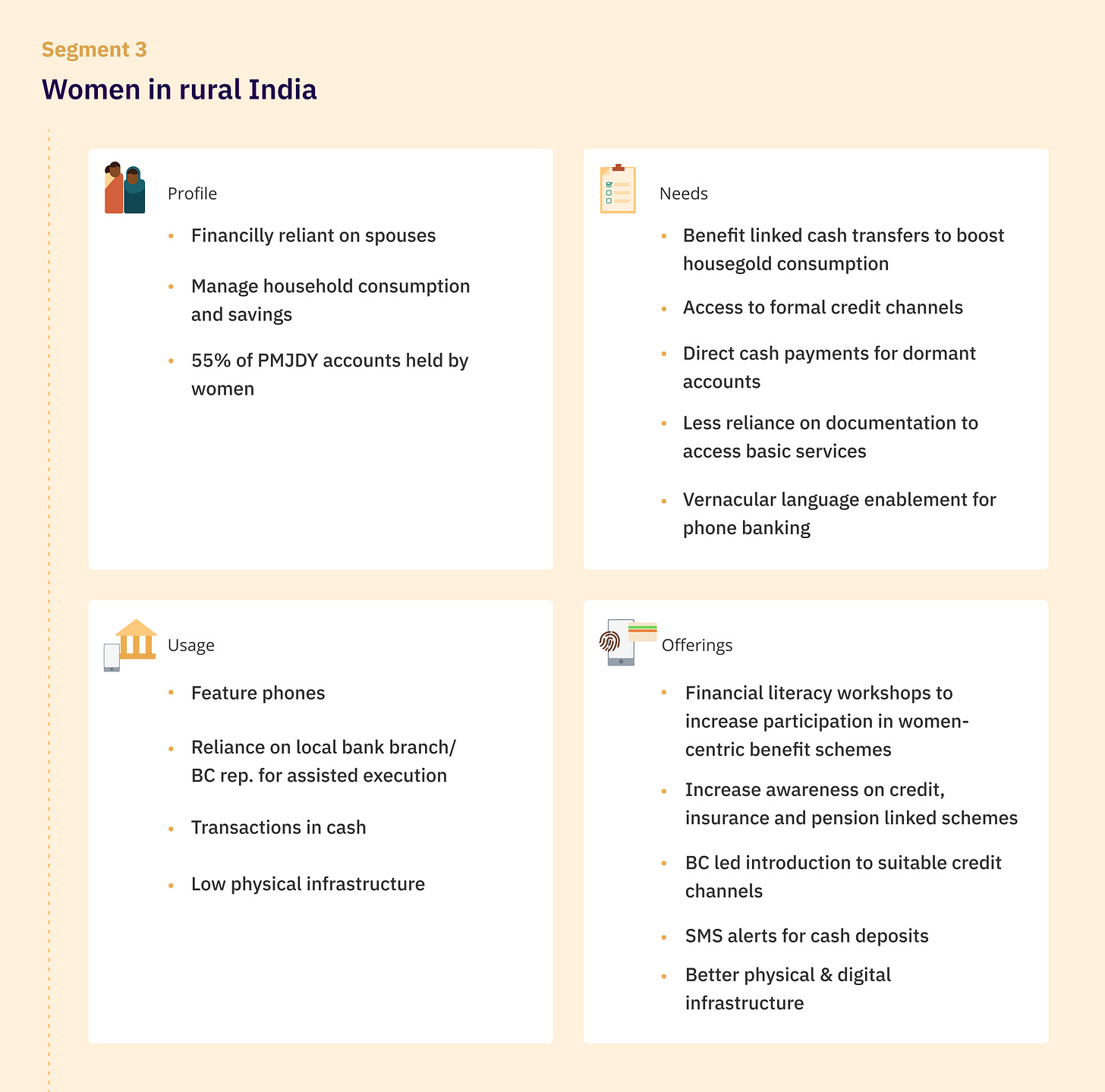

In terms of access to financial services, Bharat has indeed witnessed progress. To put this into perspective - the average distance of an unbanked village to the nearest village or town with a bank has declined from 43.5 km in 1951 to 4.3 km in 20191. Over 80% of the Indian adult population is now banked as compared to 35% in 2011. PMJDY (or “Modi Khata”, as it is popularly referred to in rural India) alone has resulted in over 430 Mn bank accounts, of which 55.4% are women account holders2.

Today, we can cite numerous case studies of success such as Digital villages in Karnataka, Smart Villages in Gujarat, and disbursement of Government subsidies via Direct Benefit Transfer schemes.

Statistics are helpful to give us a bird’s eye view. Most often, though, real stories lie behind the numbers. So, let’s look at what this progress has meant for rural India, in providing financial and economic independence. That, after all, is the essence of financial inclusion.

Bharat + Banking – A myriad of complexities

The National Strategy of Financial Inclusion (2019-2024) specifies three dimensions for quantifying the progress of financial inclusion – Access, Usage, and Quality. We’ll utilize these dimensions to provide brief sketches of some interesting and complex subtleties of serving Bharat.

Access with ease:

Kelavali is a small village situated in the Raigad district in the Konkan belt of Maharashtra. With a population of under 500 people, Kelavali has an adivasi community of daily wage farm workers, called Katkari, who typically earn between INR 250 – 500/- per day (roughly INR 11,000 per month). Most residents of Kelavali village have access to feature (non-smart) phones.

Access to mobile banking then is a far cry. The option to avail facilities at the nearest bank branch requires the Katkari community to walk roughly 10 kms and wait in day-long queues while not being dealt with in an equitable manner. This causes the workers to lose a day’s income, just to access their own accounts. A report on Deepening of Digital Payments, chaired by Nandan Nilekani, mentions the undignified treatment meted to beneficiaries of schemes, that often results in complete amount withdrawals in a single visit to the branch3.

Keeping user interest in mind is critical when providing access to services. A hybrid model with digital and physical points of access along with relevant knowledge transfer would help induct users into the financial system smoothly.

At the time PMJDY accounts were opened, the post office and cooperative banks were not a part of the scheme. If the account was opened at a far-off branch, there was reluctance to access it. However, with the 2018 launch of the India Post Payments Bank, which utilizes the vast network of 1.55 Lakh Post Offices, access to doorstep banking can become a reality for the most remote regions.

Further, with over 350 Mn feature phone users4 in India, this segment needs to be adequately educated on the possibilities for conveniently accessing banking services. Alternative payment modes can be utilized such as the BHIM Aadhaar Pay facility, wherein merchants can accept payments from customers by using their Aadhaar number, Aadhaar enabled bank account, and biometric authentication at POS itself. 5

Usage of financial services and retention:

Of the 430 Mn PMJDY accounts, 85.6% are operative with INR ~3000/- deposit per account. The number of RuPay cards issued against these accounts is over 310 Mn6. These are impressive feats given the numerous rural sub-segments.

Adding some perspective here gives a clearer picture.

‘Operative’ refers to the number of accounts with at least one transaction in the last two years – a wide timeframe of usage7. Similarly, since a significant portion of RuPay cards were issued under the PMJDY scheme, the value and volume of transactions would be important indicators of usage. Actual delivery of issued RuPay cards to users is a non-trivial process and encouraging usage is reliant on points of access such as ATMs/micro-ATMs (currently, rural centers in India have the lowest distribution of ATMs).

Delinking targets from incentives could help the system evolve more organically, to avoid bureaucratic sleights of hand like the ‘one rupee trick’, where certain PMJDY customers had INR 1 credited into their accounts without explanation8.

To effectively deliver to the last mile and inculcate the right usage patterns, the Business Correspondent model has proved a vital channel. As contract agents of banks, BCs are usually local representatives of the village/town and can help establish familiarity with the residents. BC’s can assist with basic banking services, transactions, credit solutions, utility bill payments, (including OTT subscriptions now) using digital POS devices and Aadhaar based authentication and payment facilities.

In the last 5 years, 56% of total BSBDA accounts were channeled through BCs, as per RBI’s September 2021 bulletin9. However, ongoing concerns pertaining to the model are important to resolve – suitable product recommendations by BC’s, low churn and sustainability of BC model, capacity building/training of agents, are a few that could directly stimulate usage. Introducing Bharat to a complete bouquet of financial services – bank account, credit, insurance, pension, and investment product suite – can be evangelized via the BC model using effective practices.

Information dissemination and financial literacy:

For the Katkari community, opening a bank account does not have much appeal. However, when the PMJDY was launched, several adults walked to their nearest bank branch to open an account, owing to the Rs. 5000 overdraft facility being offered.

The overdraft facility was applicable to accounts with regular transactions for at least 6 months. Without this key detail being fully understood, families like those from Kelavali village would keep awaiting their credit, leading to confusion, and eventually dormant accounts.

Financial literacy in India is said to be at 24%, as per S&P’s ‘Global Financial Literacy Survey’ – quite low for such a large population. While establishments like the National Center for Financial Education (NCFE) aim to provide materials to disseminate information via physical touchpoints, there is immense scope to utilize channels such as the BC model.

Customers need to understand the specifics of the product offering, including the nature of the product, its suitability to their needs, and implications of cost and returns. A representative such as BC can bridge this gap and bring financial awareness into the villages of Bharat. In parallel, the development of the BC framework via training, upskilling is important to successfully induct Bharat into the financial services journey from access 🡪 onboarding 🡪 usage 🡪 retention.

The new (old) Bharat

The RBI recently released the September 2021 bulletin with the computation of the Financial Inclusion Index 2021, measured on a scale of 0 to 100. The FI-Index stands at 53.9. Driven primarily by the Access dimension, FI-Access is at 73.3, while FI-Usage and FI-Quality are at 43.0 and 50.7 respectively.

In this decade, we are sure to see several more markers of progress, assuring us of the impact made on financial inclusion in India. But as we alluded to earlier, the needs of Bharat are far more nuanced, varying from one region to the next, from a dairy-farmer in one town to the daily wage farm hand in the next. In a segment comprising more than 650 Mn people, it’s tremendously difficult yet critical to unravel the needs of these regions – so that beneath all the numbers, no one gets left behind.

Neha Beri works as a Product Manager at Principal Financial Group. These are her personal views.

All illustrations designed by Prajna Nayak.

If you enjoyed reading this blog and would like to receive more such articles from D91 Labs, please subscribe to our newsletter here.