Has UPI Lite solved for small-value transactions in India?

In our first blog for the Digital Payment for the Next Half Billion series, we explain the UPI Lite model, and its various use cases along with design suggestions for payment apps offering UPI Lite.

With festive holidays around the corner, Pawan (26), a blue-collared worker1 in Delhi, returns back to his hometown of Almora in Uttarakhand, a beautiful small hill town frequented by tourists. Living in the city has familiarized Pawan with digital payments and he frequently uses popular apps such as PhonePe and Google Pay to make UPI-based payments. On returning, he is pleasantly surprised to see the familiar UPI QR Codes dotting almost every shop in the town square, spurred by the huge demand for making payments via UPI, particularly by tourists.

He goes to an eatery run by his friend Anil (30) to buy some of his favourite local snacks. Impressed by the prominently displayed QR code, he asks his friend if he can scan and pay.

“You can try if it works…” replies Anil, rather unenthusiastically. Pawan seems puzzled. To him, making a digital payment seemed like a simple enough process. He takes out his smartphone to scan through his preferred payment app. He notices that the mobile network is quite patchy. He moves around the shop to find a spot where he gets at least a couple of bars of signal and proceeds to make the payment. Pawan has a bank account with Pahadi Gramin Bank, a small local bank that is prominent in the area. He selects his account, types the payment amount, and enters his PIN. Then begins a game of roulette! There seems to be an issue with the remitter bank and the transaction does not go through. Having no other bank account to switch to on his app, he is unable to pay digitally.

Being friends, Anil trusts Pawan and asks him to pay in cash the next time he comes to the shop. Meanwhile, a couple of tourists come to the shop and also decide to scan and pay for the water bottles they purchase. Round 2 roulette begins! This time, the mobile network suddenly drops off while the payment is processing. Minutes pass by and they’re still not sure if the transaction has gone through. With no confirmation received, Anil asks the tourists to pay him by cash and gives them his contact number in case the payment eventually goes through. As the tourists leave, Anil tells Pawan that this is a frequent occurrence and that he prefers he can just receive the payment in cash to avoid inconvenience all around.

How big a deal is this really?

While UPI transactions are becoming ubiquitous and have reached over 19000 pin codes across India2, several infrastructural bottlenecks persist for end users. This becomes even more prominent in rural and remote geographies with less reliable network connectivity3.

According to the latest data released by the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), the UPI platform with over 260 million users, recorded 6.8 billion transactions in September 2022, amounting to Rs 11.17 trillion, an 85% increase (y-o-y). About 54% of these transactions by value and 75% by volume are below Rs. 2004. The rise in digital transactions is increasing pressure on bank systems. The inability of some banks in rural areas to handle demand spikes is a key reason for UPI transaction failures.

There are two kinds of failures that occur during a UPI payment — technical decline and business decline. While technical declines are caused due to issues with the bank or NPCI systems, business declines (BD) are caused due to reasons pertaining to the customer, such as incorrect pin entry or transactions beyond permissible limits. Despite significant upgrades to existing bank infrastructure, several of the top 50 remitter banks5 (in terms of volume of transactions on UPI) had technical declines of up to 15% as recently as August 20226.

This means that 1 out of every 6th or 7th UPI transaction was a failure because of system issues. Interestingly, the same banks also figure high in terms of business declines owing largely to incorrect pin entry and overshooting transaction limits which may be indicative of the high-frequency, lower-value nature of transactions that are common among the bank’s customers. The situation is still worse for smaller banks in the UPI ecosystem.

What’s the solution?

To prevent the above-stated experiences, solutions need to address two problems. First, innovate but be cognizant of inconsistent network connectivity, and second, reduce the dependence on already strained banking systems to process the growing volumes of payments.

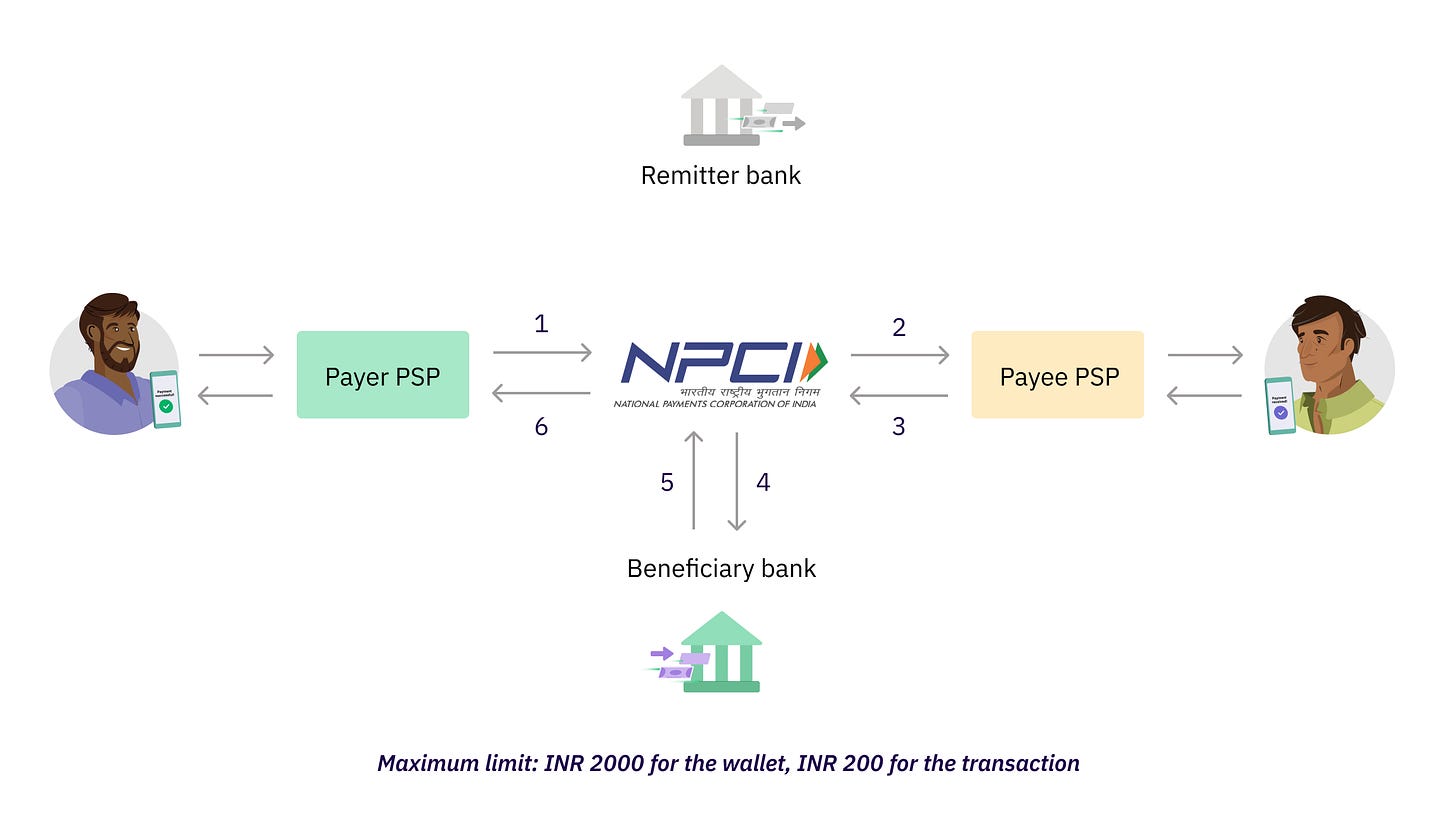

NPCI’s recently launched UPI Lite has an interesting take on addressing these challenges. UPI Lite is an 'on-device wallet' feature that will allow users to make real-time small-value payments of up to Rs. 200 per transaction (with a maximum wallet limit of Rs. 2000). On-device simply means a wallet within your UPI app, which stores its value on your device. The ‘on-device wallet’ is aimed at reducing the load on the core banking system by eliminating the need to perform multiple hops during the course of a UPI transaction. We’ve explained how this works below.

How is UPI Lite different from the regular UPI?

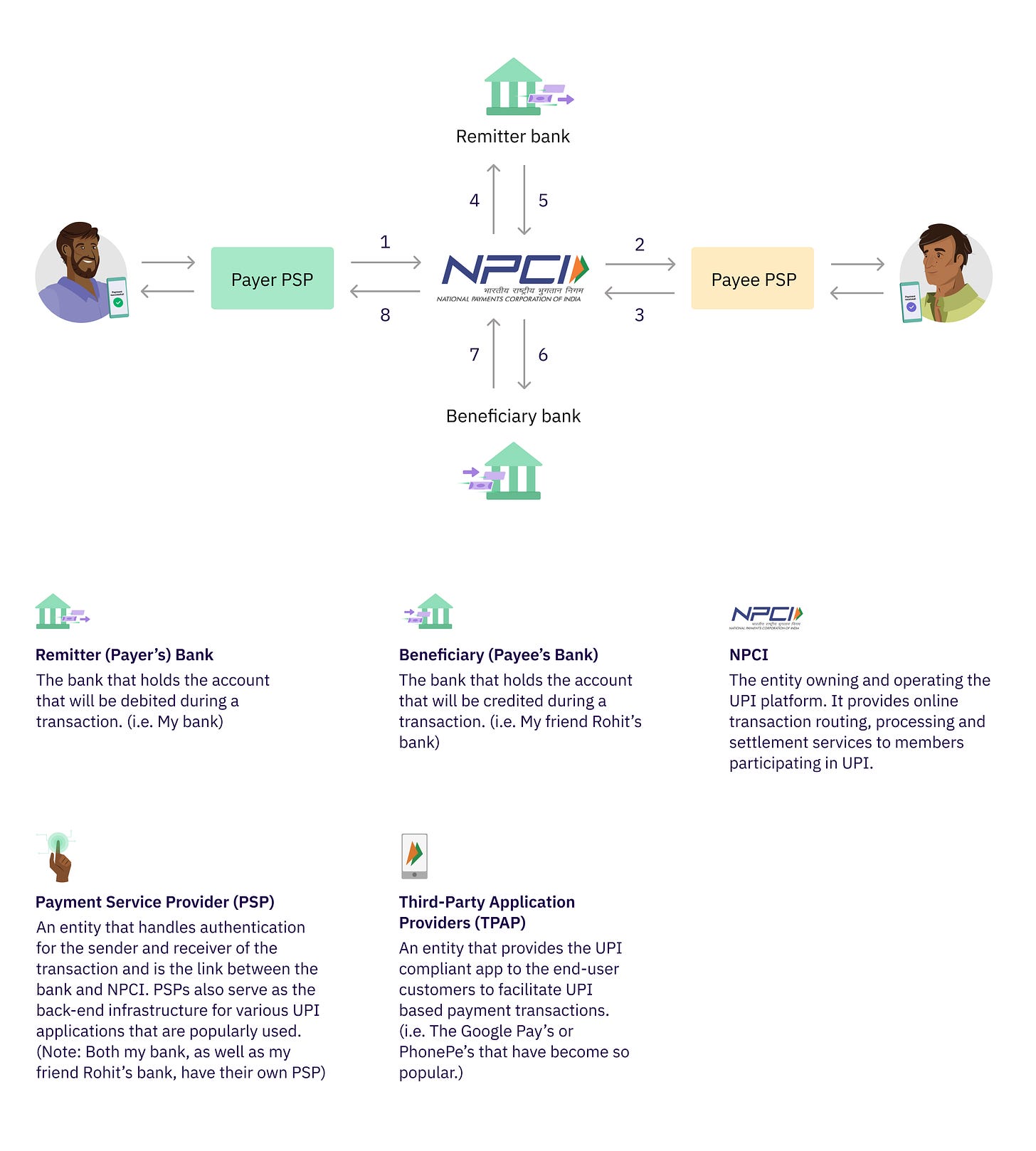

A typical peer-to-peer UPI transaction involves the exchange of real-time information between the servers of Payment Service Providers (PSP), the payer’s bank also known as the ‘remitter’ bank, NPCI’s server, and the payee’s bank also known as the ‘beneficiary’ bank.

Sounds confusing? Let’s break it down. Suppose I want to make an Rs. 1000 transaction from my HDFC bank account to my friend Rohit’s SBI account using my Google Pay application. Here are the participants involved and the transaction flow that happens.

I initiate the payment by entering the details on my Google Pay application which then connects to my bank’s Payment Service Provider (PSP).

Once my bank (through its PSP) authenticates my account information, the transaction is forwarded to the NPCI.

The NPCI then forwards this to my friend Rohit’s bank’s Payment Service Provider (which authenticates my friend’s account information).

Once both parties are verified, NPCI requests my bank (HDFC) to debit the transaction amount of Rs. 1000 from my account and confirm this debit.

NPCI then instructs Rohit’s bank (SBI), to credit the amount to his account and confirm this credit. Your friend receives an SMS confirming a successful transfer while your UPI app interface indicates a successful transfer.

UPI Lite tries to simplify this flow by eliminating certain steps in this transaction

First, as the payer, you are required to load some money into a wallet, similar to what a Paytm or PhonePe wallet used to look like. The wallet will be linked to and draw money from your bank account. The wallet stores its value on your device itself. This eliminates the need for the transaction hop needed to connect to my (payer’s) bank (Step D in the flow above) by using the value stored in the ‘device wallet’ itself. It also mitigates the chances of a technical decline from the remitter bank’s end as the banking system is not being used anymore in this step.

Mind you, unlike reports in the media, in this phase of UPI Lite, the need for network connectivity does not go away completely. You would still need the internet to load money into the wallet, verify the payee’s details and initiate the transaction. It is only at the stage of processing the transaction that the experience becomes nearly ‘offline’.

So how does this really benefit Pawan… or his merchant friend Anil… or his local bank?

How do we design UPI Lite right?

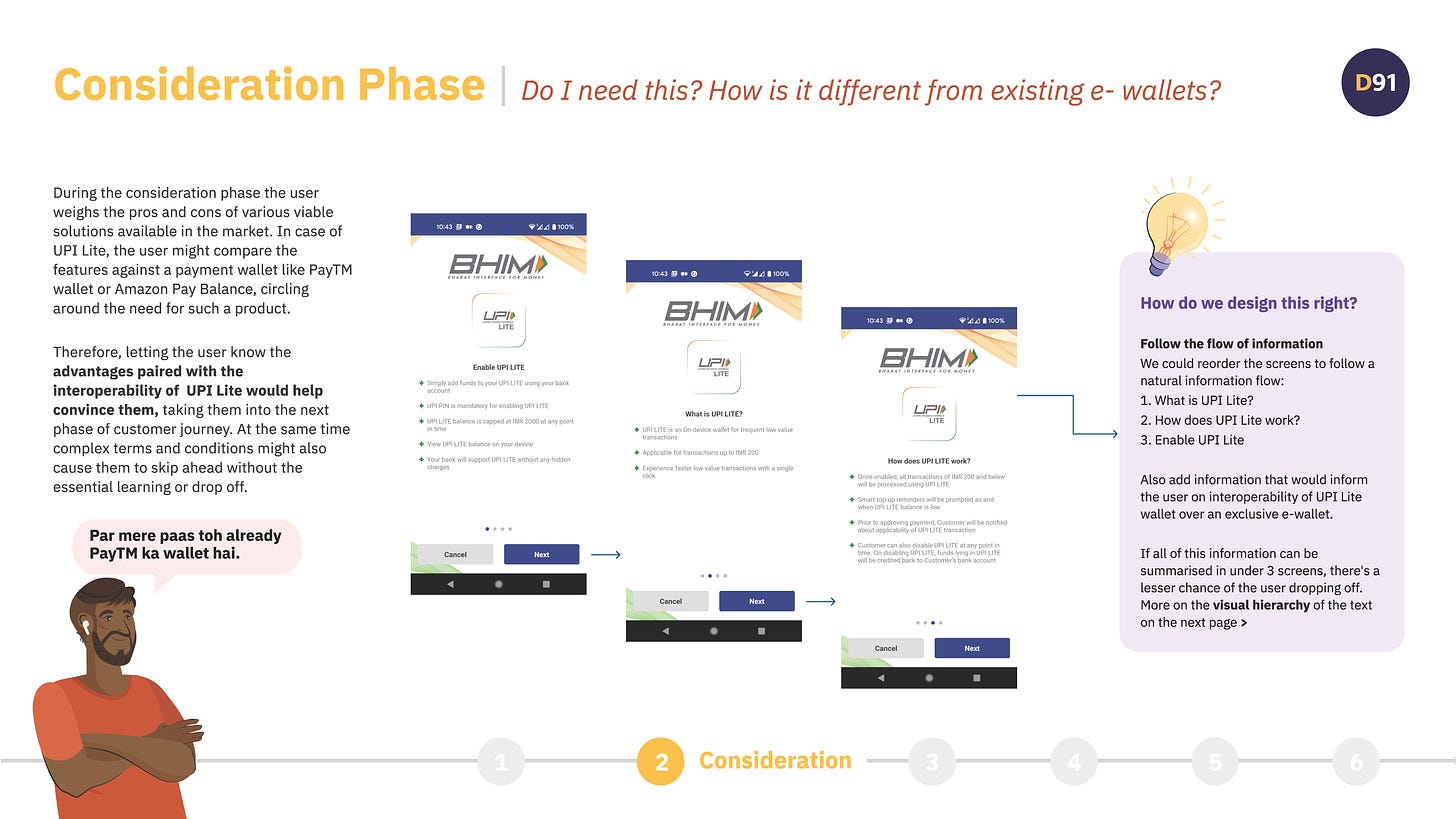

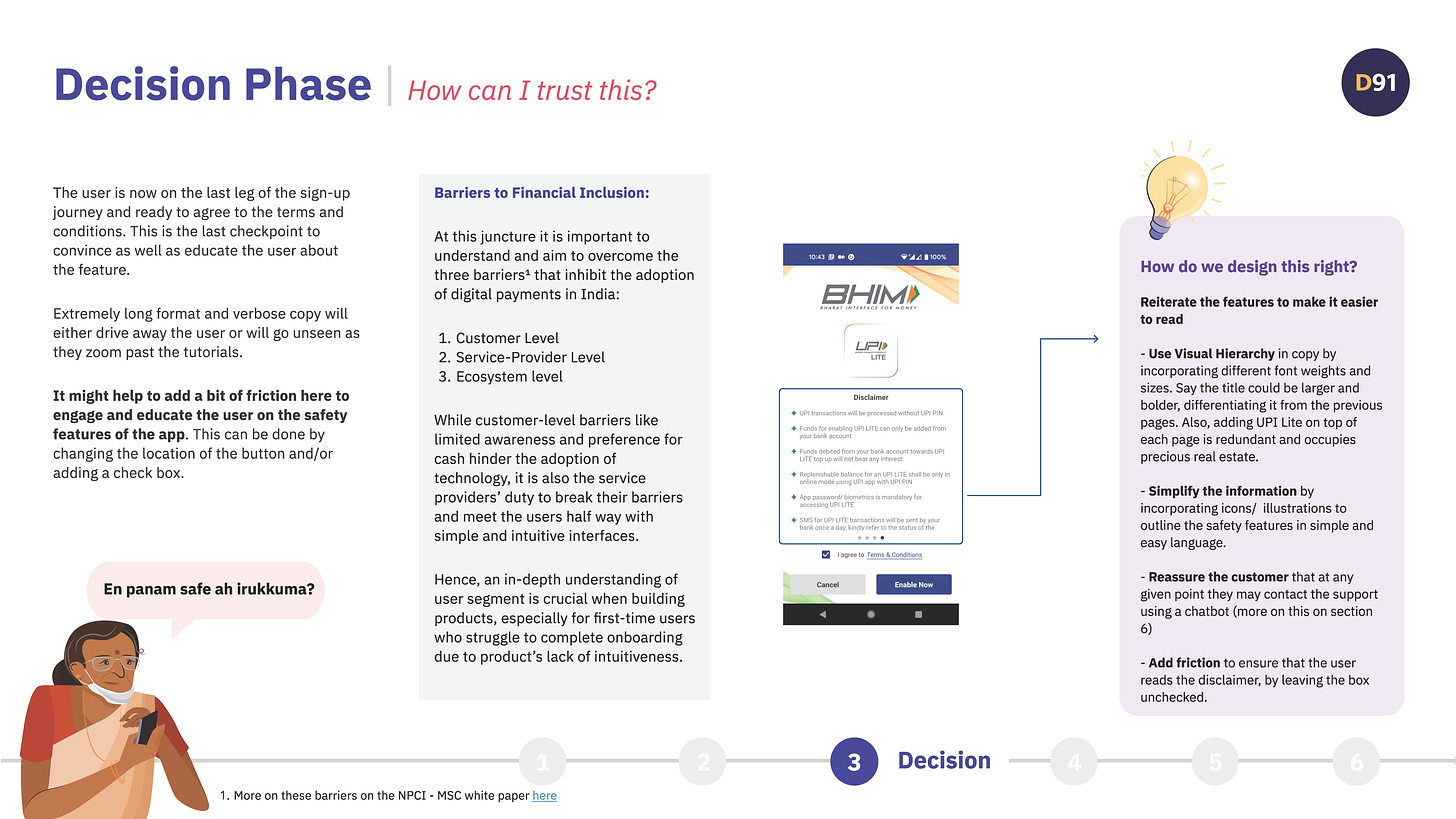

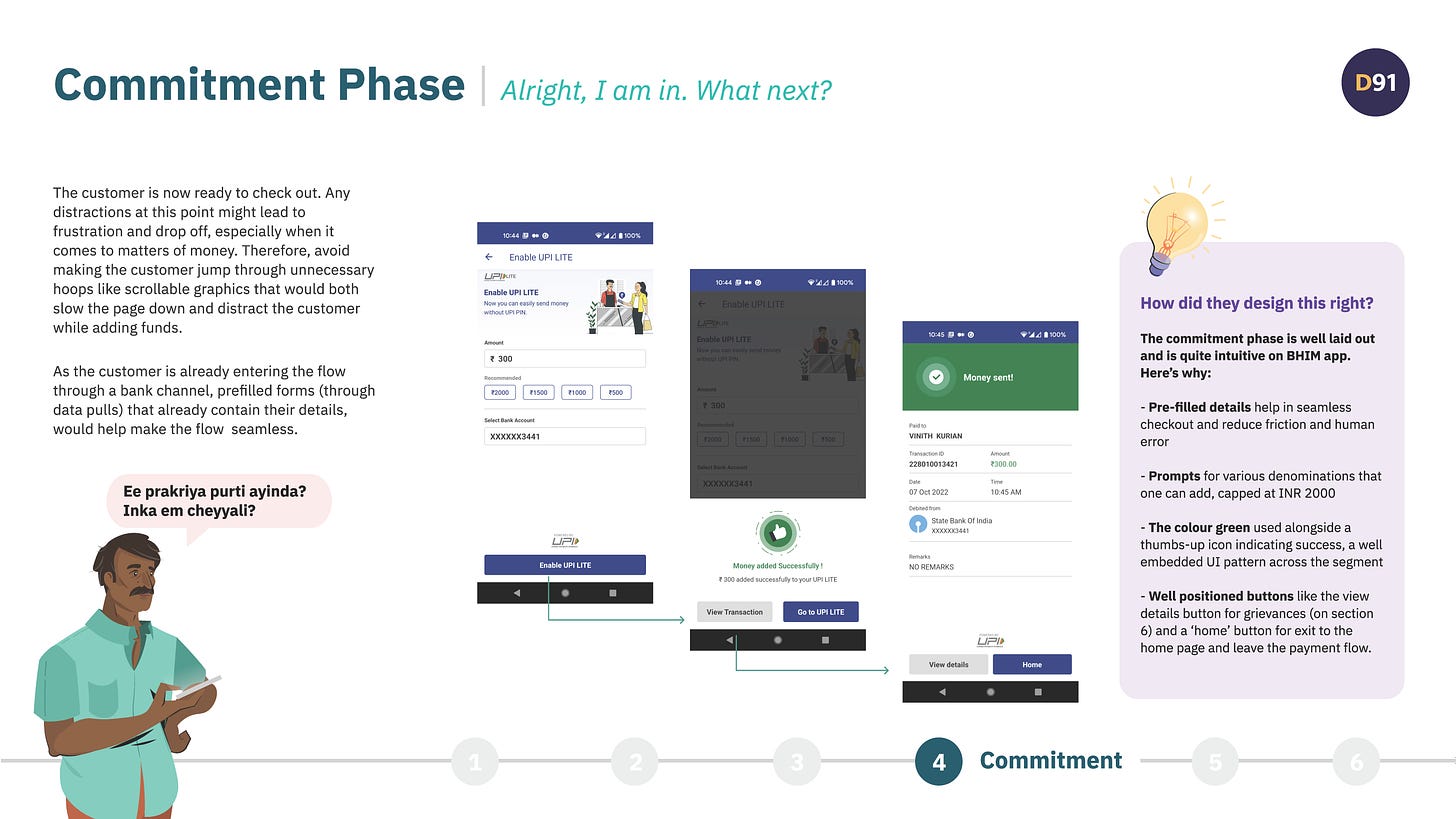

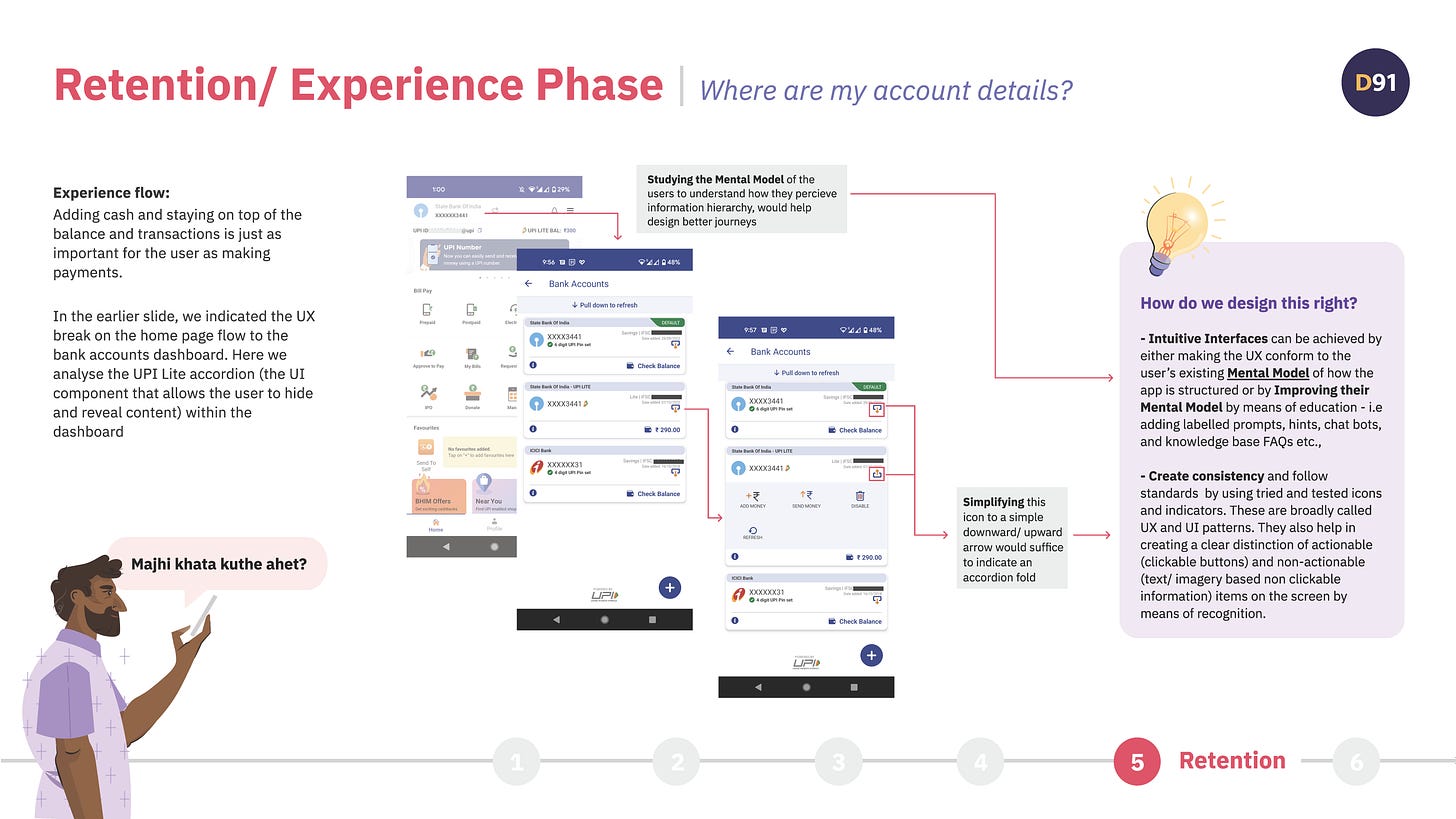

A new user of UPI Lite undergoes various lifecycle phases while interacting with the product. In this section, we provide a toolkit that outlines key steps and considerations for payment apps to make the user’s journey as frictionless as possible. For better viewing, our UPI Lite design toolkit can be downloaded here.

Simplifying solutions at the risk of consumer fraud protection?

Reports suggest that nearly 50% of financial frauds in the country are related to the UPI platform and the majority of them are through P2P transactions. The ticket size of UPI frauds is small, below Rs. 10,000. The victims typically live in metropolitan cities, are salaried individuals, and are below the age of 457. Although the UPI system’s firewalls are robust, scammers find a way to manipulate and cheat users through fraudulent links and fake resolution websites8

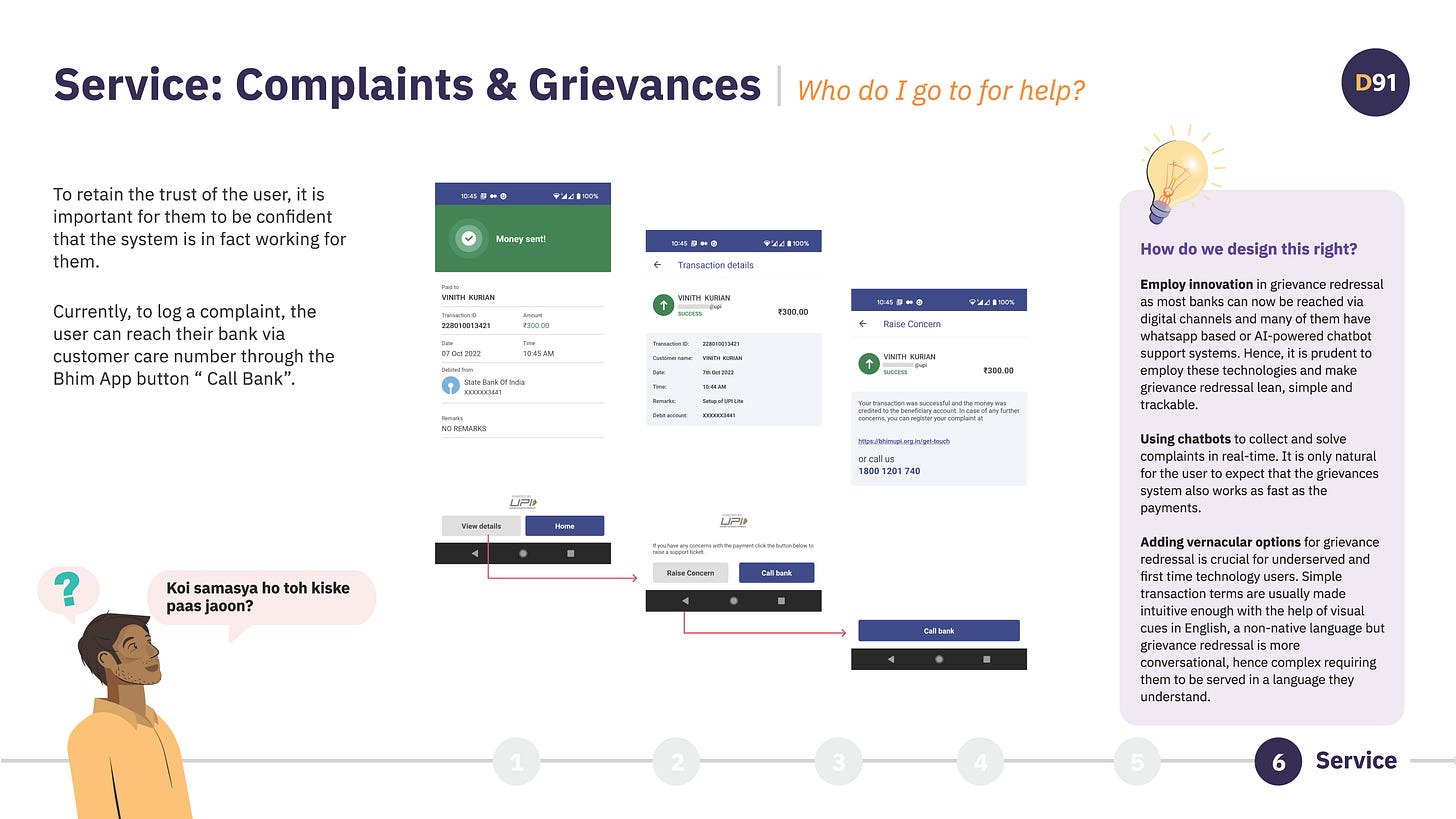

Given UPI Lite focuses on tiny value transactions that are below Rs. 200, the chances of casual fraud are higher. An innovation that can transfer payments offline, also allows fraudsters to manipulate users under the pretense of delayed payments. To make the feature safe and secure for users, a responsive grievance management system is necessary that provides timely and adequate recourse to payment-related problems.

What Next?

With the first phase of UPI Lite, NPCI has demonstrated how the platform can be made more efficient for all participants involved in a transaction. The possibilities to build on this solution are endless. What if both the debit and the credit ends of the transaction can be made offline? This would mean that the need to make a transaction hop to the beneficiary bank would also be limited, with further efficiency gains for the banking system. Pawan’s merchant friend Anil would also be able to fully reap the benefits of a near ‘offline’ transaction. NPCI indicates that Phase 2 of UPI Lite will be geared towards this.

A near offline experience would bring UPI, as a mode of payment, to resemble more closely to cash, something that rural and remote populations are more familiar with and would more easily be able to ‘behaviourally’ transition to.

Stay tuned for more updates as we closely watch this space!

Part of our series on Digital Payments for the Next Half Billion

With transactions worth INR 11.16 lakh crores clocked in September 2022, the impact of UPI in furthering the digitization of payments is unprecedented. The next wave of growth is likely to come from Tier 3-6 locations, as evidenced in the past two years wherein these cities have contributed to nearly 60-70 per cent of new mobile payment customers. Recent initiatives from the NPCI have highlighted the need to make digital payments accessible for all. With digital payments deepening financial inclusion, we explore the opportunities and challenges that these new initiatives offer to the next half billion through this series.

All artworks are designed by Geetika Shukla, Madhuri, and Roshni Nayak.

If you enjoyed reading this blog and would like to receive more such articles from D91 Labs, please subscribe to our blogs here.

To read more about our work, visit our website

You can follow us on Twitter | LinkedIn | Instagram | WhatsApp

Blue-collar workers work most often in a non-office setting (construction site, production line, driving etc.). They use their physical abilities (labour) to perform their work Examples of blue-collar employees include construction workers, machine operators, factory assemblers and drivers.

https://www.phonepe.com/pulse-static-api/v1/static/docs/PhonePe_Pulse_BCG_report.pdf

https://www.localcircles.com/a/press/page/mobile-network-problem

https://www.npci.org.in/PDF/npci/upi/circular/2022/UPI-OC-138-Introduction-of-On-Device-wallet-UPI-Lite-for-Small-Value-Transactions.pdf

Many of these banks have significant operations in remote, rural geographies.

https://www.npci.org.in/what-we-do/upi/upi-ecosystem-statistics

https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/money-and-banking/fraud-incidents-rising-with-surge-in-upi-transactions/article65413630.ece

https://the-ken.com/story/the-upi-frauds-undermining-indias-payments-fairytale/

Good piece, guys. Also great infographics.